Pope Francis: The Seraphic Pope? (Part 2 of 2)

At the end of the first part of this two-part article, I asked the question, “Is Pope Francis the Seraphic Pope of a dawning seventh age of the Church?” It’s a big question, to say the least, and I can’t provide a definitive answer. I’m not even sure it’s a good question to ask. But the apocalyptic conspiracism of the anti-Francis traditionalists, which is centred around a myth in the sense that Georges Sorel used the term, calls for a myth-building response. That is not to say I don’t stand behind what I say here. I do, but I also know that my knowledge and insight is limited. I may be wrong, and I recognize that the problems and changes that the Church is facing are bigger than all of us. But as long as grandiose thoughts are in the air, accusers are accusing, and many Catholics stand in open opposition to the Francis papacy, I might as well enter the fray, even if I am coming from a very different standpoint.

One more qualification: although I am describing Pope Francis as the Seraphic Pope, I am speaking analogically and do not intend to place the Holy Father on the same level as the highest of angels. Rather, I think that our understanding of the significance of Pope Francis may be informed by the spiritual tradition that extends from Saint Francis and his vision of the Seraph, through to the Seraphic Doctor, and beyond. That is my central claim.

In the first part of this article I looked at St. Bonaventure’s theology of history as interpreted by Pope Benedict XVI, and the significance of Bonaventure’s concept of the seventh age of salvation history and the emergence of a new era in which the People of God will await Parousia (like their departed brethren, but still in the world) in a state of general peace and contemplation, with greater insight into the truths of revelation than ever before. This is a heady vision, and one that I’m sure is discomfiting for those who are devoted to the defence of Catholic tradition, particularly if we consider that Pope Francis may be the one leading us into this new age.

At the risk of overgeneralizing, I would say that those most frustrated by Pope Francis tend to be Catholics steeped in Church history and tradition and, significantly, the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas. Although I have nowhere near the expertise in Aquinas possessed by some of the anti-Francis folks, I do understand some of their frustration. It was Aquinas that helped bring me (back) into the Church, and his Summa Theologica stands as a great rebuke to all modern moral philosophy. Although Pope Francis occasionally cites Aquinas, it is evident that some of his statements don’t fit snugly within the framework of the Thomistic doctrine that has dominated Catholic thought for so long. It is my conviction, however, that Pope Francis does not intend to leave Aquinas behind, but only to facilitate a shift to another, equally valid, way of understanding our life in the Mystical Body of Christ. It is a shift in emphasis, not a repudiation or a rupture. What we experienced in the dramatic resignation of Pope Benedict XVI and the election of Pope Francis was a shift in some ways predicted by Pope Benedict XVI himself in his interpretation of St. Bonaventure: a shift from the Dominican to the Franciscan spirit, from Aquinas to Bonaventure, and from a Cherubic pope to a Seraphic pope.

That such a shift in emphasis does not constitute a rupture or repudiation is shown by the exalted position of Bonaventure and his writings within the Church. Although Aquinas usually receives more attention from theologians, Bonaventure has long been considered his equal. In Triumphantis Hierusalem (1590), Pope Sixtus V situated Aquinas and Bonaventure as peerless Christian thinkers of their time, saying of them, “these ‘are the two olive trees and two candlesticks’ (Apoc. 11:4) lighting the house of God, who both with the fat of charity and the light of science illumine the whole Church . . . .” Etienne Gilson reiterated this idea in The Philosophy of St. Bonaventure (1924):

The agreement between [Aquinas and Bonaventure] is deep-lying, indestructibly proclaimed by tradition, which has submitted it to the test of the centuries: an agreement such that no one even in the time of the worst doctrinal conflicts has called it in question. But if these two philosophies are equally Christian, in that they equally satisfy the requirements of revealed doctrine, they remain none the less two philosophies. That is why, in 1588 Sixtus V proclaimed, and in 1879 Leo XIII repeated, that both men were involved in the construction of the scholastic synthesis of the Middle Ages and that to-day both men must be seen as representing it: duae olivae et duo candelabra in domo Dei lucentia.

. . . The philosophy of St. Thomas and the philosophy of St. Bonaventure are complementary, as the two most comprehensive interpretations of the universe as seen by Christians, and it is because they are complementary that they never either conflict or coincide. (494-95)

I was once frustrated by Gilson’s claim that the thought of Aquinas and the thought of Bonaventure are both comprehensive expressions of Christian truth but nevertheless substantially different and “never either conflict or coincide.” How could they be true and comprehensive yet so different? Further reflection has led me to see that the difference between Aquinas and Bonaventure points, analogically, to the difference between the Cherub and the Seraph, those two angelic beings of the highest order.

Bonaventure’s theology of history, as explicated by Joseph Ratzinger and described in my last post, relies on this distinction between the Cherub and the Seraph in its conception of the Cherubic and Seraphic phases or Orders of salvation history. It should be noted that these are “eschatological Order(s)” rather than “empirical” religious orders like the Dominican or Franciscan orders (45). In Bonaventure’s vision of history, which as we will remember was an orthodox modification of that of Joachim of Fiore, “The Cherubic Order, whose proper characteristic is speculatio, is represented by the Franciscans and the Dominicans. The coming final Order will correspond to the Seraphim; it will be ‘Seraphic.’ The question as to whether it has already begun or whether it is entirely of the future is left open” (Ratzinger 49). While both the Dominicans and Franciscans are still part of the Cherubic Order, the Franciscans under Bonaventure understand St. Francis as the herald of a future Seraphic Order. Certainly Aquinas’s thought may be placed firmly within the category of the Cherubic, with its emphasis on speculatio, while Bonaventure’s thought contains the seeds of the Seraphic. According to Ratzinger’s interpretation of Bonaventure, the proper characteristic or “proper activity” of the Seraphic Order will be sursumactio (an ascent of the mind to God) (52). The seventh age in salvation history will be “a time of contemplatio, a time of the full understanding of Scripture, and in this respect, a time of the Holy Spirit who leads us into the fullness of the truth of Jesus Christ” (55). Thus, the intellectual path from the Cherubic to the Seraphic is one from speculatio to sursumactio. Bonaventure’s Itinerarium mentis in Deum (The Journey of the Mind into God), which is a guide to an intellectual and spiritual ascent toward God through the contemplation of the great chain of being, is presumably at least an anticipation of this sursumactio.

To further understand the difference between the Cherubic and the Seraphic, we can also look to scripture and other sources in the Catholic tradition. Pseudo-Dionysius the Aeropagite, in his The Celestial Hierarchy, describes the Cherubim in the following manner:

The name cherubim signifies the power to know and to see God, to receive the greatest gifts of his light, to contemplate the divine splendor in primordial power, to be filled with the gifts that bring wisdom and to share these generously with subordinates as a part of the beneficent outpouring of wisdom. (162)

St. Augustine describes the Cherubim in similar terms, as “the seat of God” and the “fullness of knowledge.” He explains: “. . . some, conversant with the Hebrew tongue, have interpreted cherubim in the Latin language (for it is a Hebrew term) by the words, fullness of knowledge. Therefore, because God surpasses all knowledge, He is said to sit above the fullness of knowledge” (“Exposition” 3). In the Old Testament, the Cherubim are the guardians of Eden (Genesis 3:24), and on the lid or Mercy Seat of the Ark of the Covenant, two golden Cherubim are made according to the following instructions: “And the cherubims shall stretch forth their wings on high, covering the mercy seat with their wings, and their faces shall look one to another; toward the mercy seat shall the faces of the cherubims be” (Exodus 25:20).

The Cherubim thus possess great knowledge, but are also guardians of this knowledge. Certainly, Aquinas possessed many of the characteristics of the Cherubim. His thought displays a vast “fullness of knowledge” regarding the faith, based on systematic reasoning or speculatio, and those following in the footsteps of the Angelic Doctor have often acted as guardians of the truth. By analogy, it may be said that Pope John Paul II and Joseph Ratizinger (as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and as Pope Benedict XVI) also possessed the characteristics of the Cherubim, in that through prudential wisdom and a profound understanding of the faith they protected Catholic orthodoxy during times of great upheaval in the Church and in society.

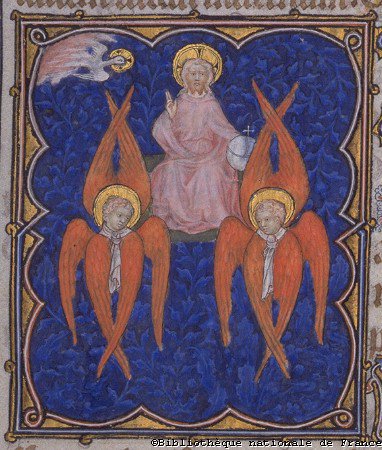

The Seraphim, while they are also of the highest order of beings, are essentially different from the Cherubim. Perhaps the most memorable image of the Seraphim comes from Isaiah 6:1-4, in which they are described as crying out the hymn that we recognize from the Sanctus:

In the year that king Uzziah died I saw also the Lord sitting upon a throne, high and lifted up, and his train filled the temple.

Above it stood the seraphims: each one had six wings; with twain he covered his face, and with twain he covered his feet, and with twain he did fly.

And one cried unto another, and said, Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord of hosts: the whole earth is full of his glory. (Isaiah 6:1-4)

Dionysius, in The Celestial Hierarchy, describes them in the following way:

For the designation seraphim really teaches this—a perennial circling around the divine things, penetrating warmth, the overflowing heat of a movement which never falters and never fails, a capacity to stamp their own image on subordinates by arousing and uplifting in them too a like flame, the same warmth. It means also the power to purify by means of the lightning flash and the flame. It means the ability to hold unveiled and undiminished both the light they have and the illumination they give out. It means the capacity to push aside and to do away with every obscuring shadow. (162)

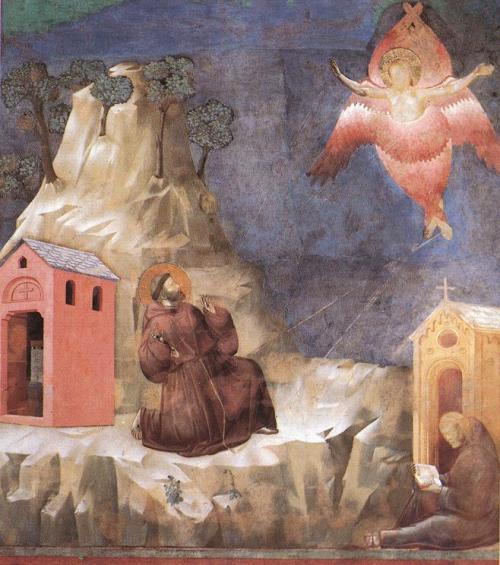

Heat, movement, flight, illumination of “every obscuring shadow,” closeness to God, and ecstatic joy: these are the characteristics of the Seraphim. The image of the Seraphim is associated with the Franciscan Order because of St. Francis’s vision of the Seraph at Mount Alverna. Bonaventure, who was Franciscan Minister General and the first biographer of St. Francis, is known as the Seraphic Doctor in part because of this connection. Pope Francis is most directly associated with the Seraph in his choice of pontifical name, but also in being a Jesuit, given the powerful influence of St. Francis as a role-model for St. Ignatius of Loyola.

The characteristics of the Seraph, I propose, may be summarized in a single word: joy. Basking in the radiance of the Lord, the Seraphim sing to each other as they fly, “Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord of hosts: the whole earth is full of his glory.” They praise God unceasingly, and they praise all of His creation. This holy joy, or Seraphic joy, is fundamental to the message of the Francis papacy. Encouragement of such Seraphic joy in the People of God is its central mission.

Pope Francis, as is obvious from his encyclicals and exhortations, such as Evangelii Gaudium (The Joy of the Gospel), Laudato si’ (Praise Be to You), Amoris laetitia (The Joy of Love), and Gaudete et exsultate (Rejoice and Be Glad), seeks to enkindle a joy that is often sadly missing from Christian life. In Evangelii Gaudium, speaking of the titular joy of the gospel, Pope Francis asks the simple question, “Why should we not also enter into this great stream of joy?” (EG 5). He envisions a form of evangelization that will illuminate the world: “Christians have the duty to proclaim the Gospel without excluding anyone. Instead of seeming to impose new obligations, they should appear as people who wish to share their joy, who point to a horizon of beauty and who invite others to a delicious banquet” (EG 14). This is no mere pep-talk. It echoes the call of St. Francis, who proclaimed (according to Bonaventure) the coming of a new eschatological order through the example of his life and work.

Seraphic joy allows one to see the beauty in even the humblest aspects of our environment. Like the Seraph, like St. Francis, and like Bonaventure in Itinerarium mentis in Deum, Pope Francis encourages the cultivation of a mystical appreciation of God’s work in nature. In Laudato si’, drawing inspiration from St. Francis, Pope Francis states, “When we can see God reflected in all that exists, our hearts are moved to praise the Lord for all his creatures and to worship him in union with them” (LS 87). Later, connecting his line of thought to a quotation from Bonaventure’s Itinerarium mentis in Deum, he states,“The idea is not only to pass from the exterior to the interior to discover the action of God in the soul, but also to discover God in all things” (LS 233). Pope Francis’s message is that by withdrawing from an inherently worldly focus on technological achievement we may begin a global spiritual ascent that starts with the contemplation of nature and allows us to share in the song of the Seraphim, “the whole earth is full of His glory!” That was also the message of St. Francis and Bonaventure.

Joy brings a sense of exhilarating movement, and with joy we no longer have feet of clay. Joy allows for abandonment to flight. We see this abandonment to flight represented in the way that the feet of the Seraph are covered by its lower set of wings, and this is the meaning behind Pope Francis’s statement that “time is greater than space” (EG 222-225). It does not point to a Hegelian concept of history, or to postmodern relativism, but rather to the simple fact that without time there is no life, no movement, and no joy.

There is something child-like about this Seraphic joy, and the joyful enthusiasm of the Seraphim for the Father. When a human father comes home from work, the children circle around him. They receive a burst of energy and can’t help but vocalize their thoughts in their excitement. The Seraphim feel this constantly, circling around the Father as they call to each other. This is the type of relationship that Pope Francis encourages us to have with God. Consider the Holy Father’s comments on November 28, 2018, when a disabled 6-year-old boy climbed on stage during the general audience at Paul VI Hall. Pope Francis let him play, let him toddle around the stage, and reflected, “When Jesus says we have to be like children, it means we need to have the freedom that a child has before his father.” In Gaudete et exsultate, Pope Francis says of God the Father, “We need to lose our fear before that presence which can only be for our good. God is the Father who gave us life and loves us greatly” (GE 51). Later in the same document, he remarks that we should allow ourselves to feel this childlike joy, and not to be ashamed of it: “With the love of a father, God tells us: ‘My son, treat yourself well… Do not deprive yourself of a happy day’ (Sir 14:11.14). He wants us to be positive, grateful and uncomplicated: ‘In the day of prosperity, be joyful. . . . God created human beings straightforward, but they have devised many schemes’ (Eccl 7:14.29)” (GE 127).

Such a focus on flight and movement, admittedly, does seem to point away from what Bonaventure (according to Ratzinger) identifies as one of central characteristics of the Seraphic Order—that the seventh age will be a “a time of contemplatio.” This apparent conflict, however, is recognized by Pope Francis himself, and he stresses in Gaudete et exsultate that contemplation and action are entirely compatible, both being required of Christians. He says, “It is not healthy to love silence while fleeing interaction with others, to want peace and quiet while avoiding activity, to seek prayer while disdaining service. . . . We are called to be contemplatives even in the midst of action . . .” (GE 26). This was also at the heart of St. Francis’s mission: the fusion of contemplation and action.

The joy that Pope Francis encourages is not an irresponsible or escapist giddyness, or blind spiritual happiness that ignores suffering. With joy, properly understood, there is no abandonment of the cross. Spiritual joy may exist even in the midst of suffering. This one of the messages behind St. Francis’s own vision of the Seraph at Mount Alverna, which is described by Bonaventure in his biography of the saint:

. . . on a certain morning about the Feast of the Exaltation of Holy Cross, while he was praying on the side of the mountain, he beheld a Seraph having six wings, flaming and resplendent, coming down from the heights of heaven. When in his flight most swift he had reached the space of air nigh the man of God, there appeared betwixt the wings the Figure of a Man crucified, having his hands and feet stretched forth in the shape of a Cross, and fastened unto a Cross. Two wings were raised above His head, twain were spread forth to fly, while twain hid His whole body. (139)

Note how the image superimposes the pierced, outstretched hands of Christ crucified over the spread wings of the Seraph, and consider how St. Francis was given “wings” in the form of the stigmata. The cross is a symbol of both suffering and flight; in order to fly, we must take up the cross. And such flight does not allow us to soar above the concerns of humanity. Seraphic flight is flight to and around God, and to and around others. It allows for closeness, and warmth. The Seraphim circle the Lord, and when the Seraph visits St. Francis it occupies “the space of air nigh the man of God.” As Pope Francis says, drawing on the model of his namesake, “Jesus wants us to touch human misery, to touch the suffering flesh of others” (EG 270). We too must not be afraid to get close to others, and to share spiritual warmth—even in something as simple as the Sign of Peace during mass.

Seraphic joy is not boastful; it is always accompanied by humility. Even the Seraphim, in their place of activity so close to God, cover their faces and feet. Their very closeness to God only makes their radical difference from God more apparent. They do not (at least in Isaiah) gaze intimidatingly upon lesser beings, hoping to hold them in a state of frozen awe. Seraphic joy is the antidote to clericalism, to the wiles of the accuser, and to that narcissistic urge to make the world small in order to reign unchallenged in one’s own domain.

Isaiah feels unworthy, but the Seraph, acting on behalf of God, sears his mouth with a hot coal, causing no pain but burning away his sins (Isaiah 6:7). Echoing the Seraph’s mercy, as well as that of St. Francis, Pope Francis has made mercy central to his pontificate. This is the subject of his powerful apostolic letter Misericordia et misera (Mercy with Misery), in which he announced that he would extend two provisions granted during the Jubilee of Mercy: permission for all priests to grant absolution to those who confess to having procured an abortion, and permission for priests in the Priestly Fraternity of St. Pius X to validly administer the sacrament of reconciliation. Indeed, Pope Francis’s two most controversial modifications of Church teaching revolve around the concept of mercy. The first is the change to the Catechism that declares the death penalty to be “inadmissible.” The second, which is more complex, is the alteration of discipline regarding divorced and remarried couples, as outlined in Amoris laetitia and made explicit in the guidelines created by the Buenos Aires-area bishops. This pastoral approach to divorced and remarried couples involves not an act of mercy on the part of the Pope or Church, but is rather part of a call for Catholics to trust in the mercy of the Father: permission to hope that God will not reject those divorced and remarried couples who, for the most compelling of reasons, are unable to live together in continence as brother and sister. This call for Catholics to trust in the mercy of God, to be like children before a loving Father, was echoed during a touching moment in 2018, when Pope Francis was approached by a tearful little boy who wanted to know if his recently-deceased father, who died an atheist but still had his children baptized, is going to heaven. The Pope, after consoling the boy, assured him that “God has a dad’s heart. And with a dad who was not a believer, but who baptized his children and gave them that bravura, do you think God would be able to leave him far from himself?” This is not false charity or mercy. It is a simple acknowledgement of the Christian belief that God is both just and merciful—that we always have reason to hope, and to trust in God’s fatherly love. Without that hope and trust, are we really Christians?

The shift from the Cherubic to the Seraphic, from speculatio to sursumactio, may be uncomfortable to some. I’m sure many will find this post incomprehensible in its apparent lack of theological rigour. But there is a logic behind the theology of St. Bonaventure, and behind the Francis papacy. No, it is not a strictly Thomist logic, but it is still grossly unfair to suggest that Pope Francis has no theology. His theology is the product of Seraphic joy. It ascends, and does not retreat into theological disputes over the letter of the law. In Gaudete et exsultate Pope Francis remarks:

For happiness is a paradox. We experience it most when we accept the mysterious logic that is not of this world: “This is our logic”, says Saint Bonaventure, pointing to the cross. Once we enter into this dynamic, we will not let our consciences be numbed and we will open ourselves generously to discernment. (GE 174)

Those who are worried about protecting the Church may have good reasons. But the Church has been in a defensive position for too long. Insularity, exclusiveness, and quests for purity are not legitimate options for change. The Church must enter a new phase, and break from its feet of clay. You can call it the Francis Option, or the Bonaventure Option, but in the end it’s not really an option.

WORKS CITED (apart from the documents of Pope Francis)

St. Augustine. “Exposition on Psalm 99.” Translated by J.E. Tweed. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol. 8. Edited by Philip Schaff. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1888.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. <http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/1801099.htm>.

St. Bonaventura. The Life of Saint Francis. Temple Classics. Trans. E. Gurney Salter. London: J.M. Dent and Co., 1904.

Gilson, Etienne. The Philosophy of St. Bonaventure. Trans. Dom Illtyd Trethowan and F.J. Sheed. London: Sheed & Ward, 1940.

Pseudo-Dionysius, the Aeropagite. The Celestial Hierarchy. Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works. Trans. Colm Luibheid. New York: Paulist Press, 1987.

Ratzinger, Joseph. The Theology of History in St. Bonaventure. Trans. Zachary Hayes O.F.M. Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, 1971.

Pope Sixtus V. Triumphantis Hierusalem. Papal Encyclicals Online. http://www.papalencyclicals.net

“Pope charmed by ‘undisciplined’ hearing impaired child.” 28 November 2018. Nicole Winfield, Associated Press. https://cruxnow.com/vatican/2018/11/28/pope-charmed-by-undisciplined-hearing-impaired-child/

‘Is my dad in heaven,’ little boy asks pope.” 16 April 2018. Cindy Wooden, Catholic News Service. https://cruxnow.com/cns/2018/04/16/is-my-dad-in-heaven-little-boy-asks-pope/